Ideally, energy models are a tool that inform design and lower a building’s operating costs. In reality, whether it’s due to value engineering or disconnects among team members in the design and construction process, they end up being used mostly as a check box for permit acquisition. However, as Michael Giulioni from Neighborhood Development Company shows, an energy model can also be leveraged to secure increased private lending to create a better project.

“With a new regulatory target, I'd rather put up the money up front to have higher confidence and avoid retrofitting once the building is constructed. Doing this kind of activity earlier means problems get solved earlier.Michael Giulioni, Neighborhood Development Company

Project teams typically view energy models as a compliance requirement to receive building permits and as an afterthought thereafter. However, a recent affordable housing project showed that doing a simple energy model early and committing to using it as a tool for decision-making in the design and construction process can lower long-term project risk and increase financing. Consider how Neighborhood Development Company (NDC), a DC-based real estate developer, discovered the value of early energy modeling in the process of securing financing for a new affordable housing development at 1164 Bladensburg Avenue NE.

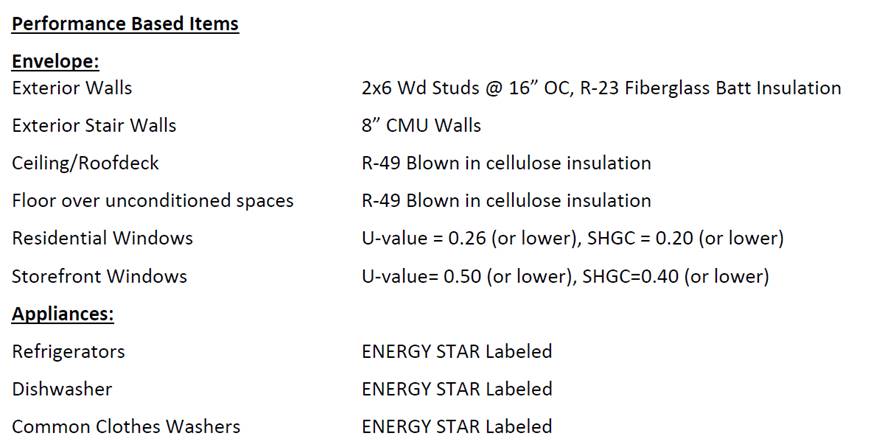

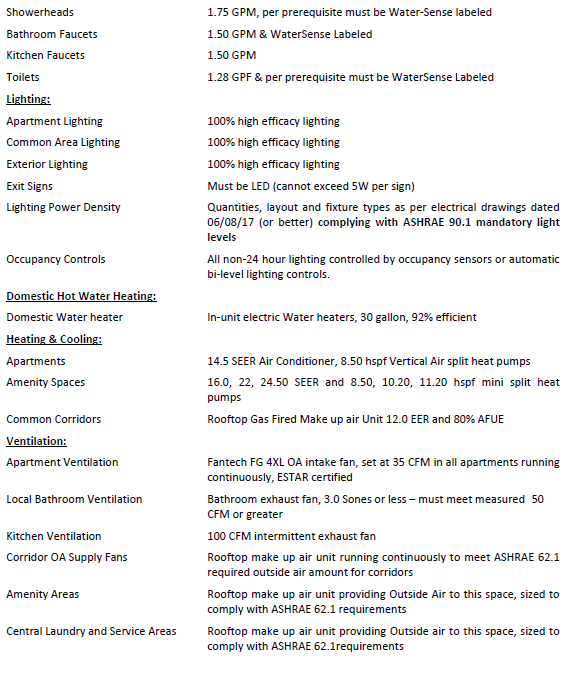

NDC was seeking to build 65-units of long-term affordable housing for seniors. To qualify for Low Income Housing Tax Credits, NDC needed to meet energy standards—in this case, Enterprise Green Communities Criteria. This meant that NDC would be investing in green building practices, such as energy-efficient designs and equipment. One of the project investors wanted to pursue mezzanine financing, a type of secondary loan, through DC PACE, a District program to provide funding for clean energy building upgrades. As part of the schematic design phase, NDC hired a sustainability consultant, MaGrann Associates, to do a black box energy model, which is required to access PACE funding.

Unfortunately, PACE financing did not end up being a fit for the project, which meant Michael Giulioni, Director at NDC, needed to find another way to raise additional capital. Giulioni worked with the Bladensburg project’s financial advisor, Jordan Bishop at Audubon Enterprises, to find a creative financing solution. They realized that their energy model showed the project to be less risky than what they had originally presented to their primary lender, JP Morgan Chase. The energy model projected lower operating costs and thereby increased net operating income (NOI) and lower debt service coverage ratio. Therefore, it showed the reduced financial risk for all parties. Giulioni and Bishop proposed that JP Morgan provide a greater initial loan to cover the higher up-front costs for the performance-increasing building features, and used the energy model as an indicator that the increased loan amount would be a lower-risk investment than the lower, original loan amount. The lender accepted the energy model as a rationale for improving the terms of the loan, and approved a higher amount, eliminating the need for a secondary financing product that they had originally sought through PACE.

NDC plans to replicate the process of using an energy model to aid in conversations with investors, to enhance their capital stack on future projects. With the lessons learned from this project, NDC has taken a greater interest in energy-efficient design as a way to provide predictability and savings in long-term operating costs as well as to get ahead of regulations like the District’s Building Energy Performance Standard. The lower energy costs also mean future building operating reserves can be lower since operating reserve requirements are proportional to the level of operating costs. This means cash can be invested in other projects.

The key innovation was completing the basic energy model at an early stage and incorporating it into financial assumptions. Giulioni reflected that “It’s worth the investment to understand the energy situation sooner. It’s important to engage in a discussion with your lenders. It isn’t really out of the norm. The lender doesn’t care about the equipment or how you get there. They just want to hear the finance assumption.”

About the Project

“Reserved for seniors aged 55+ 65 long term affordable homes in the Trinidad neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The community will be 100% age-restricted to households aged 55 years and older, and all the apartments will be leased to households earning less than 50% of the Area Median Income. The building will contain 13 Permanent Supportive Housing units with services provided by Community Connections.”

Project Team

Owner: Joint venture with Neighborhood Development Company with Enterprise Community Investments Inc. and Audubon Enterprises as equity partners.

Lender: JP Morgan Chase

Government Partners: DCHFA and DCHA, and DHCD

General Contractor: Hamel Builders

Property Manager: Residential One

Architect: Grimm + Parker Architects

MEP Engineer: Magrann Associates