Recorded November 9, 2021

Speakers

- Theresa Backhus, Associate Director of Outreach and Engagement, Building Innovation Hub

- Linda Toth, Associate, Energy and Sustainability, Arup

- Kim Cheslak, Director of Codes, New Building Institute

Event Takeaways

How might a building designed and built to DC’s Energy Conservation Code fare with respect to the Building Energy Performance Standard (BEPS)? The Hub hosted a recent webinar to examine the issue in depth.

Linda Toth, Associate, Energy and Sustainability at Arup, a Transformer-level member of the Hub, welcomed attendees and set the stage by reminding us that about 80 percent of today’s buildings will still be utilized as existing buildings in 2050, so the design and construction sectors have an immense opportunity to rapidly push performance towards energy efficient and low carbon solutions. Arup is demonstrating leadership in many ways, one of which is performing whole carbon life cycle assessments (LCAs) on all of their building projects beginning in April 2022.

Get more details about this topic in our resource.

Kim Cheslak, Director of Codes from New Building Institute then guided participants through the differences and alignments between BEPS and DC Building Code, including details on permitting, design, construction, commissioning considerations, milestones, tools and resources. The presentation is worth watching in its entirety, but here are some of the key takeaways:

1. Building code alone will not get us where we need to go

Buildings represent 71% of carbon emissions in the District, and through the Clean Energy DC program, it has targets to reduce these emissions and achieve carbon neutrality by 2030. While building codes in the District begin to address these emissions, building performance standards get us there faster.

The 2017 energy code increases stringency but, by itself, it is still not enough to reach those targets. While project teams can control lighting, water heating, and HVAC through design, there is little to no control over building users (equipment and plug loads, aka “unregulated loads”), and user activities are an ever-growing proportion of total building energy use after construction. Thus, the BEPS picks up where code leaves off and addresses post-occupancy operational energy use.

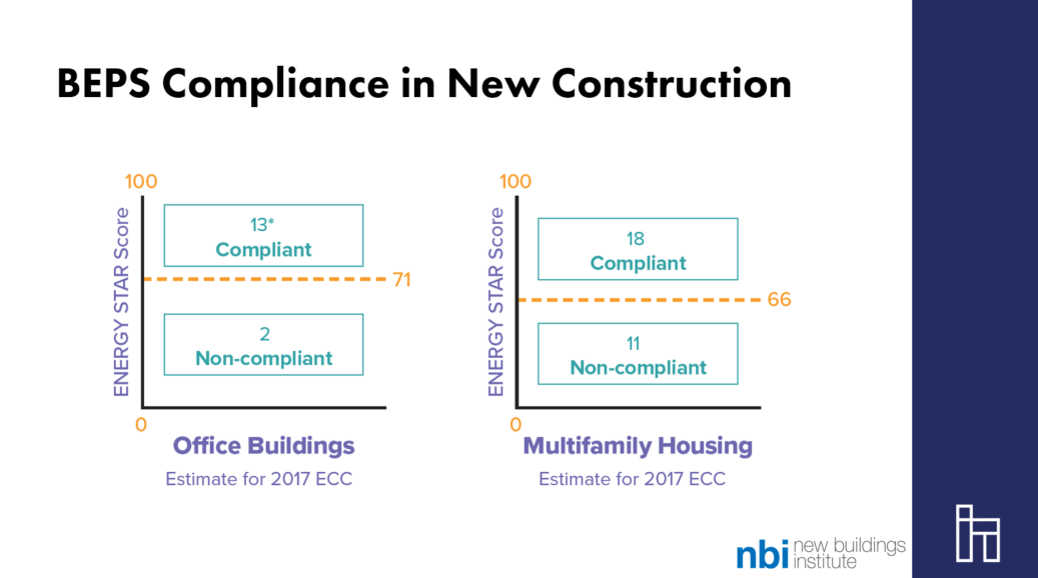

2. Buildings constructed to code are not guaranteed to meet the BEPS

According to a recent analysis of DC’s buildings, it is highly likely that code-built office buildings will meet the BEPS in the first cycle, but it’s not a guarantee. Additionally, many of the same office buildings could become non-compliant as the BEPS minimums (standards) become more stringent over time. The same analysis indicated that multifamily buildings designed to code minimums are less likely to meet BEPS, even in the first cycle.

For all building types, unregulated loads are a significant factor when it comes to meeting the BEPS, but they are not much accounted for in code. While the District’s Energy Conservation Code does include some requirements, such as ENERGY STAR appliances and auto-off plugs, codes don’t regulate occupancy patterns, operating hours, fuel type changes, or equipment and appliance usage. Therefore, users can create a high energy load once the building is occupied. These factors are, however, accounted for in the BEPS ENERGY STAR score.

Cheslak further explained that the code’s compliance paths have varied impact on long-term performance relative to BEPS:

- The prescriptive compliance path results in varying levels of performance outcomes depending on which measures are pursued. Long-term performance and operational impacts must be taken into consideration as specific measures, such as optimizing the envelope design, are chosen for a building. There are also building design factors that are not included in the prescriptive path that will ultimately affect a building’s operational performance, such as building massing and orientation, and HVAC system efficiency over the lifespan of the building (and, thus, multiple BEPS cycles).

- The performance path is a comparative, not predictive, model because it uses a hypothetical building to determine code compliance. Tools like ENERGY STAR Target Finder can be used alongside the compliance model to estimate potential ENERGY STAR scores once operational. It is also important that modeling is iterative, not static, and that weather data, building operational schedules, temperature setpoints, occupant density, and other key data points are as possible. , however ENERGY STAR score and BEPS use actual energy use intensity.

The key lesson is that design team needs to factor in operational energy use for long-term BEPS compliance, and to understand the implications of each code compliance path. While the focus of this discussion is on code-compliant buildings meeting the BEPS, it’s also important to note that a building designed with only BEPS in mind may not actually meet code.

3. Developers and designers need to future-proof new buildings

Because BEPS regulates the actual performance of a building, it’s essential to think “beyond code.” As soon as a building is built, it becomes an existing building. Thus, design teams need ensure that new buildings will not have to immediately change their relationships to real world conditions, operations, and performance. This means taking a long-term view of performance and factoring the BEPS cycles into the initial budgeting and design process of a new building. Specifically, this means focusing on envelope optimization, high-efficiency heating and cooling systems (not the federal minimums), and modern, grid integrated controls to allow tweaks and shifts in operations in response to changes.

One challenge is that the future BEPS metrics and thresholds are unknown. Architects, designers, and engineers need to keep in mind that BEPS will evolve over time to continue making progress towards the District’s goal of carbon neutrality. This includes the possibility of moving towards electrification requirements and/or embodied carbon metrics. Some ways to build in flexibility for changes such as these include submetering EV car charging infrastructure, distributed generation like rooftop solar, and real-time energy management to respond to energy grid conditions. Also, project specifications should be written to include additional requirements for operator training. These strategies may not be required by current code, but they are best practices and will help DC buildings prepare for the future.

Learn More

For more details about the concepts discussed in this presentation, check out the following resources:

- DC Regulation Basics

- Where DC’s Building Code Meets BEPS: Future-Proof your Buildings

- DC Code Updates for Engineers

- BEPS Standards and Compliance Rules “plain speak”

- Draft BEPS Compliance Guidebook “plain speak”

- New Buildings Institute: resources, case studies, codes and policies

Contact kim@newbuildings.org for further information about DC codes, or Hub staff for general inquiries.